In the 1950s my mother was a student at C. F. Mott Teacher Training College in Liverpool, where she was taught by Miss Muriel Attlee. An inspirational teacher, Miss Attlee – or “Moo” as she was known to her friends – remained in touch with many of her former students, including my mother who continued to visit her until her death in 1992 at the ripe old age of 95. From childhood I knew her as “Auntie Moo”. Although she ended up teaching religious studies, her first love was history and she was delighted when I took a history degree. She read and commented on every essay I wrote, but sadly died just before I graduated. Reading a book about the early years of university education for women in England reminded me of Moo as she was a student at Oxford University during the First World War. I realised that I knew nothing of her background and how she came be be among that early cohort of women students, so decided to put my genealogy skills (and spare time during the coronavirus lockdown) to use and see what I could find out.

Miss Muriel Attlee with my mother, c.1990

Moo was born on 9th December 1896 to Thomas Morris England Attlee and his wife Edith Isabel, nee Bolton. She was the second of their three children; her brother Charles Melville Attlee was nearly two years older, and a younger sister, Edith Marjorie was born in January 1900. The sisters were close all their lives, and in their old age Moo lived with Marjorie (I’m pretty certain I remember her as Marjorie rather than Edith) and her husband Frank, a retired farmer. When Moo was born the family lived at 21 Braithwaite Road, Sparkbrook, Birmingham; this had been the Attlee family home since at least 1881, when Thomas lived there with his own parents, Thomas and Charlotte, and his brother, another Charles. After his father’s death in December 1892 the younger Thomas remained at Braithwaite Road and brought his new wife there when he married in 1893. Thomas’s mother Charlotte presumably continued to live with her son and his family until she died in 1898, aged 81.

17 and 19 Newhall Street, Birmingham (Credit: Tony Hisgett, Wikimedia)

In 1881 Thomas’s occupation was given as chartered accountant’s clerk and his father, the elder Thomas was then a public accountant, have previously worked in a number of different clerical roles. By 1890 Thomas had qualified as a chartered accountant and was a partner in the firm of Attlee, Hill and Wheeler with offices at Newhall Street in the city centre. Presumably he was a successful accountant as he continued to practice from offices in central Birmingham for the rest of his lengthy career, and by 1908 had moved his family to a large, double fronted, detached house at Elvetham Road in Edgbaston, where they spent the next 30 years. Edith Attlee’s widowed mother, Isabel Jane Bolton, was at Elvetham Road with her daughter’s family when the 1911 census was taken, so it may be that she was living permanently with them.

Why did the family send Moo to Oxford? Clearly she came from an affluent, middle class family, who were able to afford to send both her brother Charles – who studied at the University of London – and herself to university. Moo attended Edgbaston High School for Girls, which had been founded in 1876 to provide girls with the same level of education their brothers received. A successful student, in 1914 she won a school scholarship for the best result in the Lower Oxford and Cambridge Certificate. Highly intelligent and educated at a school which prided itself on academic results, she must have been well aware that university was an option for her, but it would have needed her family’s backing (especially her father’s) to commit resources to further education for their daughter. Apparently that backing was there, and at some point during the First World War she began studying at St. Hilda’s College, Oxford. I wonder if he was an enlightened Edwardian father who valued education for women, or whether she or her teachers had to persuade him?

St Hilda’s College Library (Credit: Wikimedia)

Oxford in the Great War by Michael Graham includes an anecdote from Moo that I remember hearing from her. By 1917 fuel supplies were very limited, and undergraduates were given just a small bucket of coal to last the day, leading the women to pool resources and work together in one room to keep warm. Despite the cold they were expected to appear for dinner wearing evening dresses. Moo asked the Principal for permission to wear cardigans and was brought to task for complaining about the cold while men in the trenches were dying. Her response was “What good will it do the men in the trenches if we die of cold?” I also remember her saying she once got into trouble for allowing a young man to walk his bicycle next to her on the way back from a lecture! Moo graduated with a BA in July 1921. She must have finished her degree earlier than this, but Oxford only permitted women to graduate from October 1920, and this would have been her first opportunity to receive her degree.

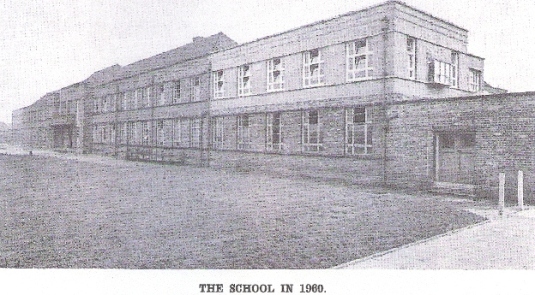

Queen Mary High School (Credit: Liverpool Schools Website)

After Oxford she travelled for a time. I know she visited Italy for some months, and she also travelled backwards and forwards to Canada between 1922 and 1924. Her occupation was given on passenger lists as “teacher”, and it appears she was teaching in Canada but coming home for the summer holidays. By 1925 she was teaching at Queen Mary High School for Girls in Liverpool. Why Liverpool? Almost certainly it was because her brother Charles was also teaching there, presumably at the University. Charles’s studies were interrupted by the war, when he spent some time in the Naval Wing of the Royal Flying Corps, but like his sister he was highly academic. By 1939 he was Professor of Education at University College, Nottingham, and he spent some time after the Second World War as a university professor in Egypt, probably sponsored by (or working for) the British Council there – in 1945/6 he had been considered for roles at the University of Athens and as the British Council representative in Greece, but due to a misunderstanding between the Foreign Office and the British Council this did not come off.

Moo taught at Queen Mary High School for over twenty years, becoming the Second Mistress (deputy head). She was with the school when it was evacuated to Shrewsbury in 1939, where she shared accommodation with another member of the school staff. In 1946 C. F. Mott Training College was founded to help alleviate a national shortage of teachers. At this time Moo left Queen Mary High School, so presumably she was one of the original members of college staff. The college campus centred on a large 18th century house, The Hazels, on the Prescot/Huyton border in Knowsley. Originally a women only college, it became co-educational in 1959. It was probably around this time, or soon after, that Moo retired. After her retirement she moved to the village of Aston Cantlow in Warwickshire, where her sister and brother-in-law lived. At some point, probably in the late 1970s or early 1980s she moved in with them, before spending her last years in a retirement home in Bidford-on-Avon where she complained of “creeping decrepitude” but generally remained in good health until her short, final illness. The last time I saw her, she was using the limited time her eyesight could cope with small print to re-read Dante in the original Italian. I can imagine her delight that one of my daughters (who she never got to meet) studied Italian at university and took a course on Dante.